Around the World in 20 Days

Breitling Orbiter 3's logbook

01.03.1999 - 21.03.1999

I wanted to immerse myself day after day in this flight with its adventures, my hopes, my fears... I invite you to rediscover this trip around the world with me...

Day 1

First problems, first fears...

Six hours after take-off... I keep the balloon between 7000 and 8000 m. The envelope's thermal insulation is so effective that it cuts out the effect of the sun. If I have to heat not only at night as planned, but also during the day... we risk running out of fuel before we reach our goal!

Our first real problems came at sunset: the fax machine stopped working and, outside, the satellite telephone aerial froze, rendering it unusable. But the most worrying thing was that we were consuming too much propane. As the sun disappears behind the horizon, it doesn't heat up any more and we're forced to use our burners even before it's completely dark. To top it all off, our pilot lights start working erratically. These little high-pressure flames on the roof of the capsule are supposed to automatically light the burners, which are themselves controlled by timers on the dashboard. As their name suggests, the pilot lights should never go out, but they do, forcing us to constantly use an electronic igniter to get them going again. Regularly, one of us has to leave our seat, take two steps backwards and reach for the button on the burner control panel, fixed to the wall of the central corridor next to the fuel gauges. More than exasperating when you're forced to heat every 10 seconds for six seconds, i.e. 60% of the time!

Brian Jones and I look at each other, and we're thinking the same thing: "We're in big trouble!

We can repair the fax machine. As for the antenna, it will eventually thaw out. But the manual ignition is a real nightmare. And this fuel issue is raising the spectre of running out of fuel in the very near future. Previous calculations have given us a range of 12 to 24 days of fuel. At the current rate, we'll run out of fuel in less than a week... We haven't even been flying 24 hours and already our chances of success seem seriously compromised.

All of a sudden, we don't know where to turn. We spend our time relighting the burners to balance the balloon while reprogramming the fax machine and trying to establish radio communications with the air traffic controllers on the Côte d'Azur. The Marseille control tower, overwhelmed by the intensity of the air traffic, insisted that we maintain our cruising altitude. But our burner problems are causing us to dive or climb by as much as 1,000 metres. While we wait to stabilise, we ask Marseille to allocate us a wide enough corridor for our dolphin jumps.... I go to bed at 7.45pm without being able to get any sleep... The aggressive sound of the propane jets intermittently lighting up wakes me up every time I'm about to fall asleep. I'm obsessed with our fuel consumption and my sleep remains light and restless. At one point I think I feel a sudden drop in altitude and I imagine that Brian must have switched to the next pair of tanks. If we've used up two tanks out of 32 before the end of our first night's flying, we're lost. It all started so well... Less than 24 hours after departure, it was all doom and gloom.

Day 2

Throughout this second day, we continue to have problems with the burners. We solve them by trial and error, adjusting the timers so that the residual flame from one burner stroke can ignite the next stream of propane despite the malfunctioning pilot lights. Much more worrying is the formation of ice on the fuel control unit, located on the ceiling, very close to the upper window. Between 7000 and 8000 m, it's -35°C outside...

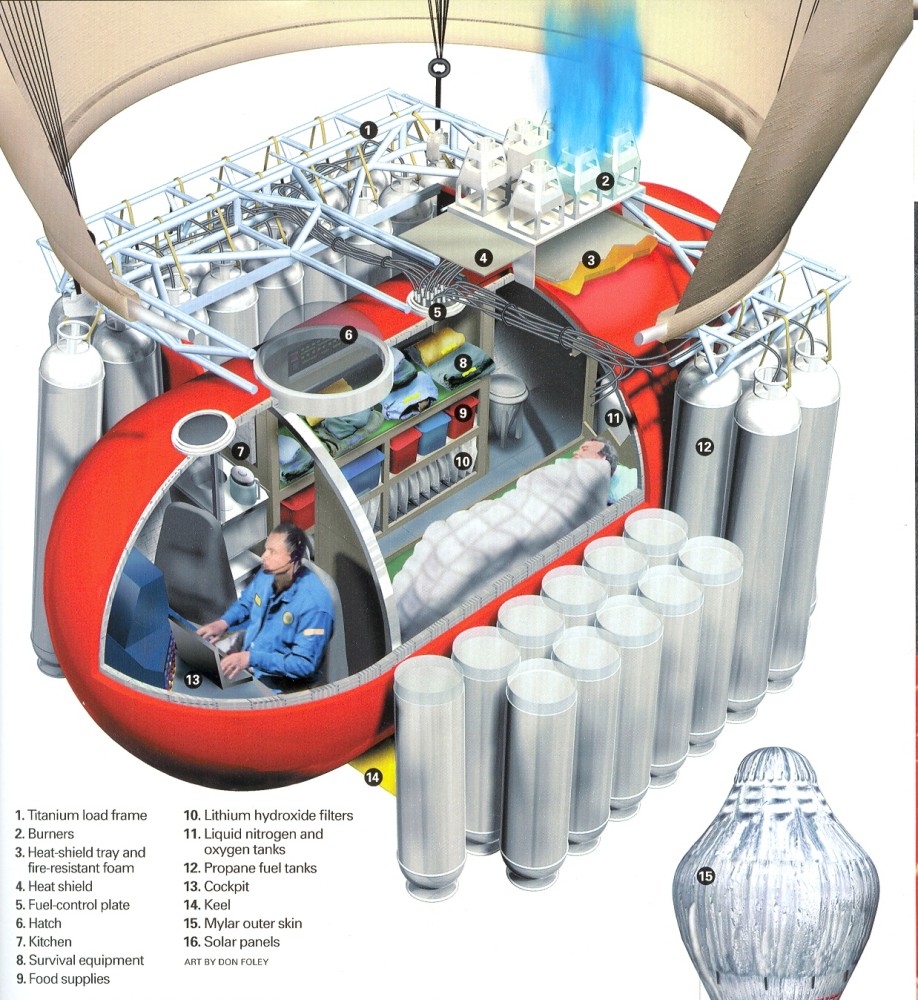

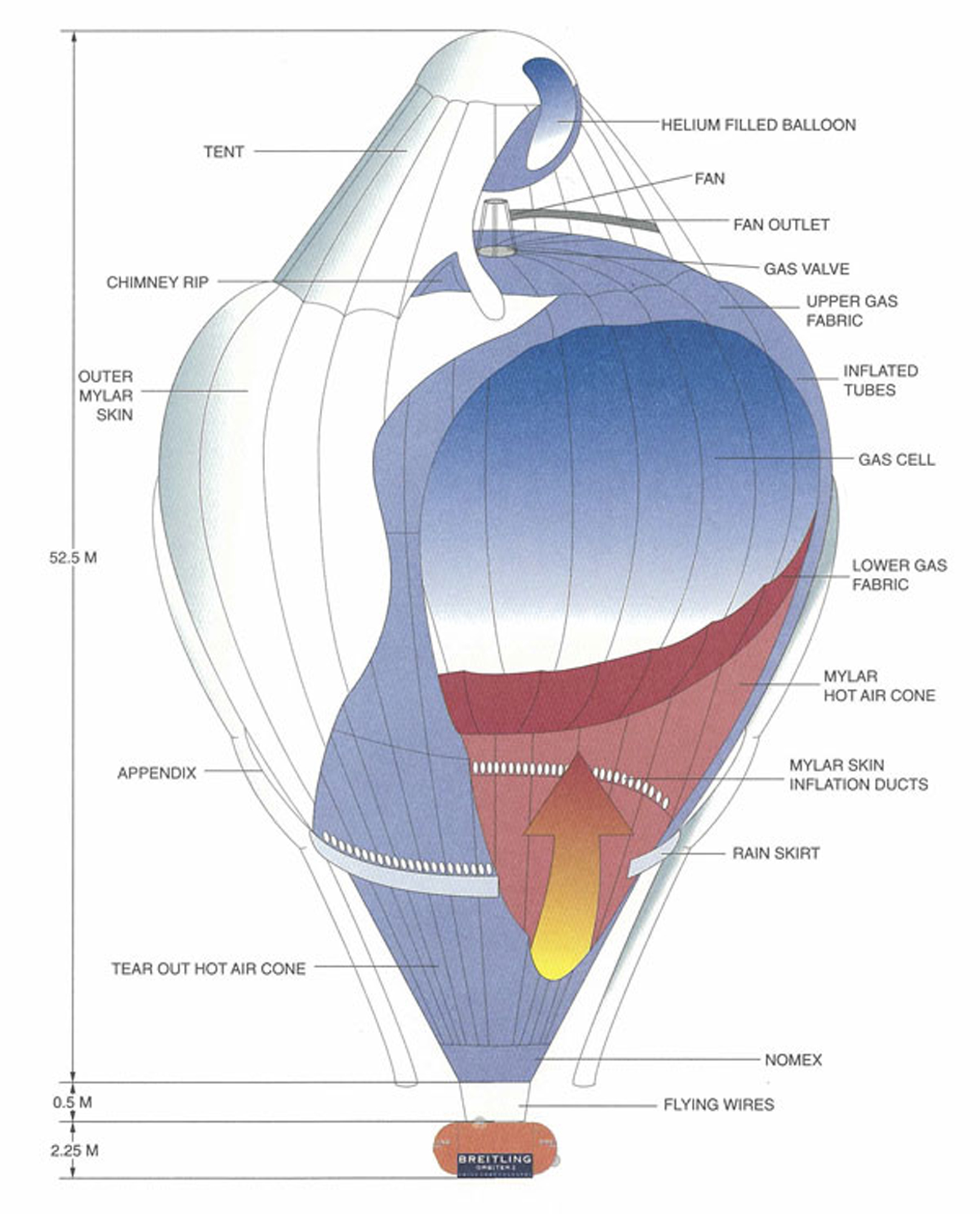

Breitling Orbiter 3 may be the most sophisticated balloon ever built, but this is its maiden flight. The manufacturer has developed its future behaviour through countless computer simulations, but no one has ever been able to test it in real flight conditions. The real test comes now. On the afternoon of the second day, we reached a speed of 49 knots. That's our record. With our eyes glued to the GPS, we watched for the moment when we would break the 50-knot barrier! At that precise moment, the control centre calls out: "Slow down! Slow down!". In spite of ourselves, we obeyed and descended from 8000 to 5000 metres. Our speed then dropped to 31 knots, then to 25... It's hard to accept slowing down voluntarily when you're trying to circumnavigate the world! "If you go any faster, you'll be heading for the Black Sea and entering China in the wrong place...". We hate the feeling of being remote-controlled... but we soon get into the habit of comparing our trajectory calculations. It's up to us to stick to the ideal route by raising or lowering the balloon. The clouds don't help us assess our speed or direction: they just sit there, behind the windows, moving at the same speed as us. Only the GPS, which tells us our heading to the nearest degree and our speed to the nearest knot, allows us to navigate accurately. On the evening of the second day, accompanied by a sumptuous sunset, we crossed the Mediterranean east of Gibraltar and entered Moroccan airspace.

Day 3

We're still heading south-west, according to the strategy defined by our meteorologists to enter China at the level of the thin corridor where we've received flight clearance. The balloon is making good progress and I only have to warm up for three and a half seconds every 16 seconds: less than 25% of the time! I've switched off all the automatic alarms and I'm keeping a close eye on the operation of the burners for constant fear of a breakdown. At sunrise, it's not without a touch of anxiety that I discover that, during the night, stalactites have grown all around the bottom of the envelope and that the cables are sheathed in ice. The ice accumulated on the balloon is in danger of weighing us down... It starts to melt under the sun, but the resulting water falls on the capsule and freezes again... Naturally, we're anxious to turn east and accelerate. Finally, in the evening, we begin to turn degree by degree exactly as the meteorologists had predicted at 22:30. We're at 6000 m on a 115° trajectory, but at only 22 knots. The considerable lead of our competitor Andy Elson, who set off well ahead of us and is currently somewhere north of Bangkok, is making us even more worried about not moving fast enough...

Day 4

The rising sun on the fourth day draws mosaics of light on the frosted portholes. Below us, the desert. Someone predicted that our interminable flight over the Sahara would be boring, given the uniformity of the landscape. Not only is the view spectacular, it's constantly changing! I spend hours contemplating it. The palette of colours is infinite. The desert is full... full of emptiness. It takes all the arrogance of human beings to imagine that a desert is empty. I think of Saint-Exupery; he followed the same route with l'Aéropostale and was stranded there because of a mechanical problem.

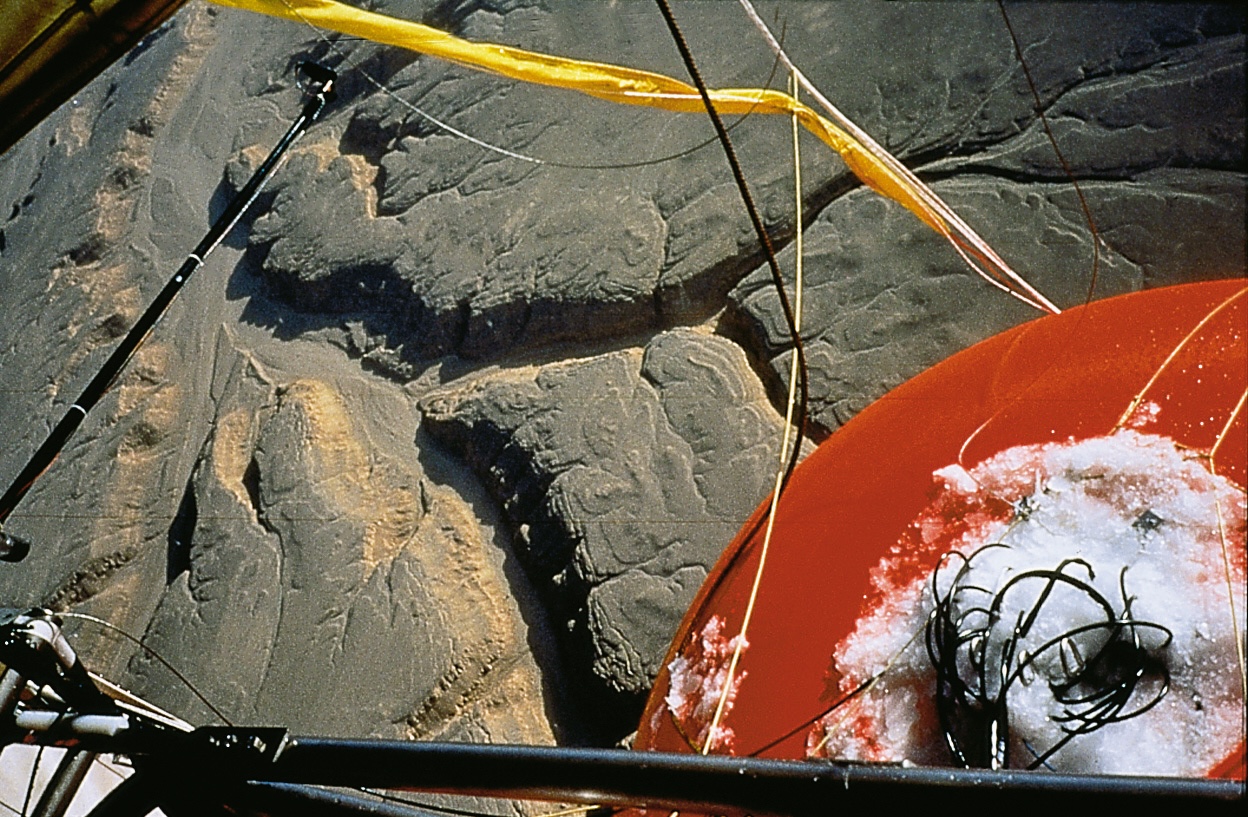

Now, we had to make a decision. Given the low altitude at which we are flying, the control centre asks us to get rid of the empty propane cylinders. It is imperative that the drop takes place over a desert area where the falling tanks are unlikely to cause any damage and where there are no clouds below us, so that we can see the ground perfectly. This can only be done by getting out of the cabin to cut the tethers. Below us, 3,000 metres... We open the roof and discover a crazy amount of ice. Three-metre stalactites connect the bottom of the envelope to the capsule. I forget all about the stress and the vertigo... Like a child, I attack the stalactites with an axe, having the time of my life!

It's snowing on the Sahara...

Brian and I managed to detach the four tanks, which ended up in the dunes. A look of doubt is exchanged... we reassure ourselves that this equipment will be buried in the sand without harming or disintegrating.

The day draws to a close. We maintain our trajectory as far south as possible and even beat our own speed record, 65 knots! The trajectory is perfect for reaching China at the right latitude...

But tomorrow, it's Libya that awaits us.

Day 5

Here we are over Libya. Richard Branson had problems flying over it, and we're having communication problems announcing our passage... as long as nobody gives us the order to land! We're going fast, over 70 knots! Enthusiastically, I share the news with HQ... but I'm quickly put on the back foot for "speeding"! Our meteorologists, Luc and Pierre, ask us to descend and slow down so as not to veer off course. Frustrating... but I trust their calculations. Libya is soon behind us, and we arrive in the land of the Pharaohs. I go to bed early, at 7pm, not suspecting that Brian is going to have an eventful night.

At 9.30pm, Brian realised that we were heading straight for the Aswan Dam, an area that is strictly forbidden to fly over: the wind was pushing us inside this 50 km radius perimeter, which is strictly closed to all flying machines... Faced with burner problems that he had to deal with, Brian moved away from the radio and the Egyptian controllers, insisting on specifying the position of the balloon, began to get annoyed. If we don't change course, the fighters will intervene. Difficult negotiations with the air traffic controllers ensued. They finally decided to reduce the ban to 30 km around the dam... Phew, we'll pass just 30 km south of Aswan...

We head for Sudan, who will completely ignores us all the way across the country.

Day 6

During the night we receive a message from Andy Elson, our competitor, who is ahead of us in his Cable & Wireless balloon. Stuck over Taiwan, he taunts us and suggests we celebrate with him when we finish second! Inimitable Andy... but between the lines, I understand that he's treading water, whereas in 48 hours we'll be arriving in China. It looks like we're catching up...

At 6 am, we are flying over the Red Sea coast. We're heading for Saudi Arabia, unless the winds take us towards Yemen. At the stroke of midday, Brian wakes up, annoyed: the condensation has wetted his whole bunk. Impossible to sleep! Bedding hung out to dry... it was like being in a dry cleaner's! Once we'd reached the Saudi coast, the rest of the day was to be one of the best on board. Together, in the cockpit, we watch the clouds, drink tea and chat about everything and anything. We're relaxed.

But not for long...

Day 7

Below us the Red Sea.

In front of us a big strip of Yemeni territory, south-west to north-east, a danger zone… supposed to be used for military training. We won't be able to avoid it… Anxiety ran high among our air traffic controllers in Geneva. All of us are thinking about the dreadful incident over Belarus in 1995 during the Gordon Bennett balloon race. One balloon was forced to land, the other was shot down, killing both pilots. Our HQ is clear : either we get permission to cross the zone, or we stop before it. Patrick, one of our flight controllers, tries to negotiate with the Yemeni civil aviation authority and Sanaa airport, asking for clearance.

Long and complicated discussions with Sanaa control tower that lead nowhere…The man on duty only spoke broken English and kept asking

"What is the balloon’s destination?"

Patrick’s answer : "It’s going round the world" ...

to get the same question back : "What is its destination? If you have a flight plan, you must have a departure point and a destination? !!!"

The man couldn’t give clearance because he lacked authority to do so… All Patrick could do was trying to gauge the man’s mentality…In the end, Patrick got the impression it will be no problem. The impression, not the certitude...In the control center, the atmosphere remained electric as we were flying over the northern edge of the prohibited zone.. Although no sign of life from Yemen, we knew from the orange light flashing on our transponder that we were on their radar as we went over…

We receive news from our competitors Andy and Colin aboard the Cable & Wireless balloon. They're in Japan, about to start the crossing of the Pacific. We are too far behind...

Brian goes to bed, unaware that the destiny of this flight is about to change...

As I am minding my own business, on pilot duty, I receive a call from HQ : Cable & Wireless is ditching in the sea, 120km away from the Japanese coast, rescue is already on its way. They're safe. We are alone in this race. I am shocked, both for my friends Andy and Colin, imagining their frustration, but also for us thinking we could run into the same issue. I see Brian sleeping in the bed, but we had promised each other we would never wake up the sleeping pilot unless it was an emergency. Finally he wakes up.

"Brian ! I have incredible news !"

Without hesitation, he replied : "Andy’s down!"

Like me, he's shocked but relieved. We were catching up, but they were still four days in front of us. We are approaching Oman, on a trajectory that is perfect to reach China at the correct entry way.

On the eve of this 7th day, more good news : Brian decides it is time for him to change underwear!

Day 8

I wake up finding out that we beat my own distance record. That's in the bag, at least !

Our meteorologists, Luc and Pierre, confirmed us that our position is perfect for entering China at the right point. By constant experimentation, I discover that the layer of wind carrying us along on the 70 degree track is only 100m ( 300 feet) from top to bottom. All the more reason to be concentrated…

Since Andy dropped out, the press is all over us, and as we are going slowly we have plenty of time to answer questions. I manage to keep track of our trajectory, which would make us reach China at 26 degrees, as requested. HQ is delighted.

All is well until it isn't. Mumbai tells us we do not have official authorisation allowing us to fly over India. We are thus banned from entering the Indian airspace, which we can't avoid. Our flight director Alan had applied for diplomatic clearance and asks for it again and again… and in the rush to get the balloon ready the matter had been overlooked. Now what ? We are about 400 km off the coast, on a waypoint for commercial airplanes...

Finally, after hours of discussions and negotiations, we are given permission to fly between 6000 and 7000m over India. All of this, we learned weeks later, at the end of our trip. Brian, who was flying, didn't know that our trip almost came to an end abruptly over the Indian ocean, because of bureaucrats.

Day 9

At sunrise, we are flying over India, To celebrate that we are back over inhabited territory, I change into clean clothes. This is a special day : it's our last one to adjust our point of entry to China. I am focused.

The inefficiency of Indian communications is driving us nearly crazy. Radio contact is almost always difficult and we are relaying via passing aircrafts. Local air controllers are demanding to know our position every ten minutes !

As I was concentrated on holding our trajectory, I suddenly hear an airplane calling me : “Hotel Bravo – Bravo Romeo Alpha, I have a surprise for you !” That's when I hear the voice of a good friend, Charles-André Ramseyer , on his way to India for work with a Swiss delegation: "A passenger saw you from the window ! He shouted:

Look, it's the Breitling balloon!

We are all in the cockpit, tears to our eyes. We see your beautiful balloon, alone in the blue sky, carried by winds so far away from our homeland." Charles-André is the person who introduced me to the world of ballooning, back in 1978. That encounter is one more little sign of fate that seemed ton mark our enterprise, I thought.

That afternoon brings us one of the most memorable moments. Too busy dealing with trajectory matters, Brian and I hadn't been focusing on the outside. Suddenly, we realised we could see, some 400km away, her majesty the Himalayas, poking through the clouds to our left...

Bangladesh welcomes us over VHF radio, wishing us all the best. It's always nice when things go smoothly with air-controllers. Our passage over that friendly country is brief. Then Indian territory again, Myanmar, soon China. The Chinese have seen us coming...

Our first interaction with them worries us :“Your balloon is heading towards a no-fly zone. You need to land immediately”

Day 10

We are flying 50km south of the limit authorised by the Chinese, at great speed and with great spirit : they’d let us in. China here we go!

This is our great advantage over our rivals: we spent months negotiating with the Chinese authorities, even going to Beijing a year earlier to talk. With my team and my wife Michèle Piccard we managed to establish a cordial but very strict relationship. We made a deal : we would fly over China in a thin corridor, below the 26th parallel. We also signed a document, after months of discussions, where we swore we would land if the wind took us north. Moreover, if the entry trajectory over Chinese territory looked wrong, we would land in India, Pakistan or Iran.

Our target ? A strip representing 5% of Chinese territory. Any other point of entry would have meant the end.

On March 10, I wake up to Brian shouting :

"We are in China !"

An unforgettable moment. A planning masterpiece from our meteorologists. On the radio, I thank everyone at HQ, knowing they are 100% behind us and with us. We still have 2400km to go over China, but we are moving so fast we are already looking at what’s ahead. In the end, the preparation for the flight portion above China was way more complicate than the flight itself.

Day 11

Just before leaving Chinese airspace, Brian checks the next map and sends a message :

"There is an issue with the new map : it’s all blue !"

In front of us : the Pacific. 12.000kms of it.

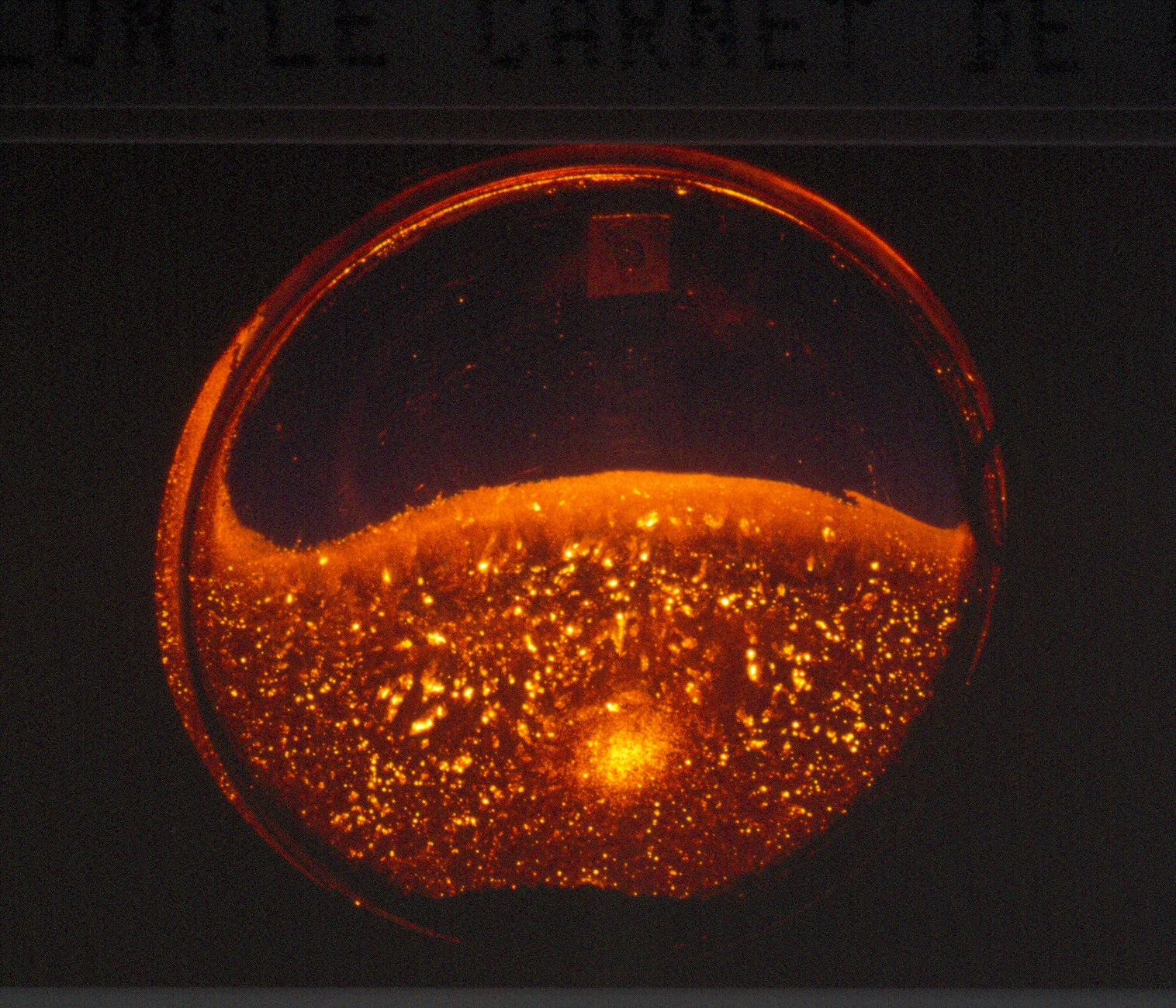

While I write about what this portion of the flight represents, I am brutally taken back to reality : huge flames are bursting into the baloon, as the electric valves are blocked in the open position. I jump to close the fuel tanks and save the silver-coloured fabric from bursting into flames. I manage to stabilise the ballon just before sun-up. My thoughts wander to the fate of Richard Branson and Andy Elson. If we could avoid these kinds of mishaps, that would be best...

In the cabin, there is no tension between Brian and I but we are both stressed and a bit frustrated with HQ over the issues we are running into but we both have ways to deal with that on our own. I meditate, he sends passive-aggressive messages back to Geneva. They answer back saying we are flying in a Japanese military area, where warfare exercices are being held involving ‘aerial combat, bombardiers, missiles, submarines’ and that we should hurry before it starts…This kind of humour would have worked with us a few days ago, after 11 days not so much…Back at HQ, we learned eventually that stress and increasing pressure on everyone made this part of the trip difficult for them too.

After flying over Iwo Jima, another of those ‘destiny-moments’… During my shift, I am now flying over the Marianna Trench. My horizontal flight is cutting through the vertical one of my father. I immediately call home, to share this moment with him. I am participating in a race, like him before me. Will I be capable of adding another win to my family’s honours? I am both hopeful and doubtful, alternating between the two. At least, after 5 years of preparation, I am getting close to the moment of truth.

Some more meteorological troubles ahead. Our meteorologist, Luc, suggests a radical change of course : forget North America, as planned, head for a jet-stream down south. A jet-stream, we soon learned, that didn’t exist yet ! Instead of flying over the US, we need flying coordinates for Miami, Havana, Kingston, Curaçao, San Domingo…In reality, we do not have many options. The route toward North America is packed with storms, which would have forced us land on water. The southern route would be longer, adding a couple of thousand miles to our journey, but safer. In theory.

I wasn’t optimistic anymore. I called my wife Michèle Piccard, telling her I thought we would crash due to the lack of fuel. She didn’t get me. She had talked with the meteorologists an hour earlier, who were sure about their route. ‘You only have to do three or four days at low speed and then, you’ll get the jet stream…’. ‘Well’, I told her, ‘ I don’t see how we can rely on a jet stream that doesn’t exist yet…’. She called Luc and Pierre again, telling them we were worried.

"Bertrand, Luc told me, do you trust me?"

"Yes, I replied."

"Then do what I said!"

To add to the stress, Brian sees huge ‘CBs’ up ahead, i.e cumulonimbus clouds, just before sunset. The same ones who took down Steven Fossett a year earlier, almost killing him.

For two days, the aluminium coating of the envelope has cut the connection with the satellite that was just above the balloon, and we lost all contact with HQ. Our heating system is failing, the temperature is just above 0 degrees, increasing our sense of isolation. We are tired and scared. The only sure way to avoid these clouds is to fly above them, but at dusk, it is impossible to see how high they reach or where they might move.

Day 12

We are trying to hold a track of 123 degrees, but we are surrounded by these CBs… Gigantic storms to the south…We had to climb as high as we could to avoid them. For three days now, most of our maps have been blue. Inside the gondola it is so cold, many things are going wrong , tank pair ran out after only 24 hours and 50 minutes of use, and Luc expects our speed to degrade from 45 knots to 35 or 30.

"Brian, are we still friends?"

"Alan, he replied, we never stopped being friends. But from time to time you can really be a pain in the ass..."

We are happy that someone like Allan, tough and strong, is there to ‘catch the heat’ from our terrible moods...

Day 13

Today, above the mightiest of oceans, thousands of kilometers from the closest land, surrounded by the deepest waters in the world…I learn that Brian is scared of water...

When I tell him “I’m a bit frightened by this wide ocean”, he replies fully honest “I’m shitty scared” !

In other news, we receive a message that struck a cord with us, coming from Neil Armstrong, wishing us good luck. Richard Branson, a rival but most importantly a friend, also writes to us. We had fun in this race against each other, and in another timeline we probably would have tried this adventure together. I remember an anecdote, at the launch of Breitling Orbiter 1. He landed in Geneva to attend, and saw a huge poster of our balloon. He took a pen and wrote ‘Good luck, dear friends. Richard Branson’. His son saw it and said ‘But at home you say you wish they failed!’. We both wanted to win, but our rivalry was friendly.

Today should be one of our last days going very slowly, towards the jet-stream that our meteorologists are betting on.

Day 14

Today is EVA day, our last one, meaning we are headed outside of the cabin, because the valves of our burners started to freeze, again. We don’t take long to fix what needed to be fixed, but what we don’t know is that the Oakland control center worried that we did not reply to their incoming calls, and raised the alarm. When an aircraft is 30 minutes behind its planned route, air controllers automatically engage rescue procedures. In particular in the Pacific, where every minute counts. Oakland calls Geneva, telling Alan, our flight director, about their intentions.

"Do you have any airplane in the region ? Alan asks. It could call my pilots on VHF radio."

"Nothing, no one ever goes down there..."

The Americans are about to send planes from Midway and the Marshall Islands when we finally re-establish contact. No one would have enjoyed paying the bill for a useless rescue mission...

Day 15

Today, we cross the International Date Line. While everyone has seen 15 sunrises since our departure, we’ve seen 16, as we had less than 24 hours between two sunrises going east. Most importantly…we’ve reached the jet-stream !!

Our meteorologists were right ! We are going fast, 180 km/h, but something else is too : our fuel reserves. We’ve used 2/3s of it, and we still have half of the world to cover...Everything now depends on our speed, on our meteorologists planning the best and fastest route possible.

If they fail, we fail.

Back at HQ however, euphoria is at its peak. The jet-stream is everything we could have hoped for, carrying us at great speed towards Mexico, and then Cuba. Greg, our air-controller on duty, recruits his Colombian wife Claudia to negotiate in Spanish with the Mexican authorities. Thanks to her, and her negotiation skills at 3am local time, we receive a laisser-passer from both countries.

We do not know it yet, but our meteorologists have just committed their only mistake. A mistake causing the most dangerous problem we will face during this adventure...

Day 16

We are flying high, on our ‘ceiling’, at 10 500m. We are going fast. Really fast. Luc and Pierre, our meteorologists were in ecstasy after their incredible gamble of sending us so far south. …But we are burning fuel, and a lot of it. Because of the clouds that surround us in the jet-stream, the sun cannot reach us and our main batteries cannot be charged anymore. We turn off the high-frequency radio, to save energy.

During the night, we reach the coast for the first time since Japan : Mexico !

Day 17

Our fuel reserves are dramatically low. To stay up and keep this great speed we have to heat the balloon up constantly. The risk is clear : going down over the Atlantic. Will we have enough propane to take us home ? The question is driving us and HQ crazy. Brian and Alan, our flight director, are exchanging messages constantly. HQ raises the possibility that, by mistake, we maybe went over our ceiling, causing the balloon to lose its bearing capacity, thus pushing us to consume more fuel.

The cabin is so cold I am trembling during my sleep. Waking up for my shift, I learn that our chances at making it all the way to Africa are thinner and thinner. I am alone, Brian went to bed. Alone with my stress. We are slowing down, going off course. We are not headed towards Africa anymore, but towards Venezuela...

In the middle of this crisis, we receive a message from the Duke of Edinburgh, Prince Philipp, asking us to accompany him when he will visit Cameron Ballons in Bristol in a few days…He adds :

"if you make it to Africa, the Queen will be there too"

The tension is having an effect on my mood, as I reply to HQ : ‘If the Queen wants to see if we make it to decide if she comes or not, it’s better if she doesn’t anyways !’

My message is received with laughter by HQ. I have other issues. I am waiting for the jet-stream to bring us back on track, but it doesn’t...

Problems are accumulating. I start to feel weak, ouf of breath…that’s when Brian wakes up, way before his shift, whispering:

"I can’t breath"

I call HQ, and learning that Michèle Piccard is there, I start crying, loudly, on the phone : ‘We are going to fail now! So close. After all these efforts. We are going south, we are short of fuel and we can’t breath’. As often, she’s stays calm and suggests I pick myself up : ‘Stay sharp, stay focused. You know how to deal with these situations, you know the drill. The weathermen are confident you’re going to get back to the jet’. She manages to calm me down, despite the feeling that I am suffocating.

It’s time for the daily update, live from Swiss TV, where my dad and our meteorologists participate. I couldn’t join for a few days now, because of the the time difference, but I am now able to join in :

"I am…in the cockpit…Brian is…trying to sleep…We are…both…out of breath…not…our best day"

Everyone starts panicking, calling doctors to have their opinions, all catastrophic scenarios are envisioned : coma, then crash into the ocean, and the eventual sinking of the cabin...

Our symptoms are not those of a lack of oxygen, but that doesn’t stop us from feeling suffocated.

We receive instructions not to talk to the press anymore, as the whole of Switzerland is only talking about our breathing problems. After the flight, we figured that we were having a pulmonary preodema, caused by the inhalitation of very dry air for too long. Oxygen masks are now helping us, as they keep humidity close to our noses.

Everyone down on earth has at least realised this is no stroll in the park : it’s difficult, and dangerous.

HQ tells us : ‘If cheering and love could be used for fuel, you would be on your second circumnavigation of the globe’.

We are feeling better, but we are still facing the same dilemma : should we go up, to rectify our trajectory, or go down to save fuel ? We decide to go down, but are now on our way south, far from the jet-stream. Our meteorologists intervene :

‘Go up, as far as you can.Go to your ceiling. You should find a stream that takes you away from Venezuela. It’s your last chance’.

Doing so, I used monstrous quantities of fuel, trying the last possible manœuvre to save the flight…Still heading towards Venezuela when all of a sudden I feel the wind turning. It happens live, on the phone with Michèle:

"I only have 50 meters left to go before the ceiling, but it’s incredibile ! We are getting back on track ! We might make it ! We might make it ! It’s a miracle!"

We are headed towards Jamaica, on our way to the Atlantic !

Late on this 17th day, we receive a message from my father :

"Victory is near. You are tired, stressed, impatient to reach the finish line. Who wouldn’t be ? Stay cautious, have the courage to help those who are helping you with everything they have to achieve your dream, by achieving it. Courage. Everyone loves you and hugs you."

Day 18

Over Haiti, we are delighted to see islands below us. If we decide not to go for the Atlantic, we will be close from land. San Domingo’s air control asks that we take him with us next time...

At HQ, they are now looking towards Africa. Trajectory is good, until I feel again a sudden change of direction towards the south. The weathermen believe the direction will be better this time if we flew lower. Time for a difficult decision : I have to vent some precious helium to lose altitude and get back on track.

Down on the ground, it’s media madness. After the oxygen drama, they are now wondering if we will try to cross the ocean or not. Our press center is invaded by journalists, just a thin wall away from our HQ and our team cannot leave the place without being harassed by reporters.

The final decision has to be made. Do we go for it ?

We agree to make the decision live, during a press-conference. Live around the world, Alan asks us our speed, our altitude and our trajectory. We answer, very factually. Alan tells us, and media : “I think you can go for it’. I answer by remembering what Dick Rutan told me, before Orbiter 1 :

"The only way to fail is to give up. And we won’t"

We are going for it. We will cross the Atlantic Ocean.

Day 19

We are targeting a landing in Mali, if we go further the ideal would be Egypt.

We are crossing the Atlantic with great speed, and at sunrise today we realise we are flying in huge clouds. Our solar panels don't work, and our cabin is below zero degrees. I write in my journal :

"I have to ignore what is happening on the ground. I prefer to forget the hopes of our team, our families and our friends. Everybody thinks that we will make it, but I cannot celebrate yet. And I am sure, once we do make it, I will still not believe it."

When Brian takes over in the cockpit, we are still in the middle of the jet-stream, flying towards Africa at 220 km/h. On the ground, madness is everywhere. We receive thousands of messages through the web. Andy Elson, our former rival, went on the BBC and said we wouldn't succeed, as our fuel reserves were too low... At his place, I would have never dared to say that and look so stupid afterwards.

When I wake up again, I promise Brian I would wake him up 30 minutes before the finish line. We have one and a half pair of fuel tanks left. I think about the 1 million dollars promised by Budweiser to the winning team. Brian and I discussed a few times, during the flight, that we could set up our own charity Foundation with that money...

Day 20

At 6am, my GPS tells me we've reached Africa, over Mauritania. The next hours, until the finish line, will be the longest of my life. 500 km to go. Terry Lloyd, a journalist, hired a plane to fly next to us up until the finish line. On the radio, he asks for an interview. He wants me to wake up Brian.

"I can't do that Terry, we promised we would wake each other up only in case of emergency."

"Please, I need him for British TV."

"I undestand, what I can do is talk really loud so he wakes up by himself."

"Scream Bertrand, scream !"

"ALRIGHT !"

As expected, Brian woke up.

Now that we are both awake, we put on clean clothes. We want to look good for the cameras. Dakar is ok with our trajectory. Libya and Egypt too.

The main problem now lies with what happens next, after we land. No one wants to see us land in Mali or Mauritania, huge empty territories but full of mines and no helicopters to come and get us. Algeria doesn't want to welcome us. Libya could be ok, but they would not let the Breitling plane in with our recovery team.

And so there is only one real option : Egypt. The farthest one. Brian had said, during his first press conference, that his dream would be to land near the Pyramids. Now, it might happen and the media are all over his prediction, but quickly a sand storm develops over Cairo and Brian's dream fades away...

We are about to cross the finish line. It's there, we can almost see it, grab it from the sky.

We cross it, around 10am.

We did it.

We hug each other, in tears, screaming :

"WE DID IT, WE MADE IT"

Live, we answer questions from all the journalists gathered in Geneva. We hear laughter, cries, screams of joy. I think of my dad, at HQ, who will still be stressed until we land. He tells me 'Bertrand, what you did is extraordinary. However, you still have to land and let me remind you of something important. You might have thought about it but..don't forget to bend your knees when you land !'

One of the greatest explorers of the 20th century is also a protective father. I only realised upon my return how tough these three weeks were for him, how much his health suffered from it. He doesn't share emotions like I do, but I know that he was worried all along...

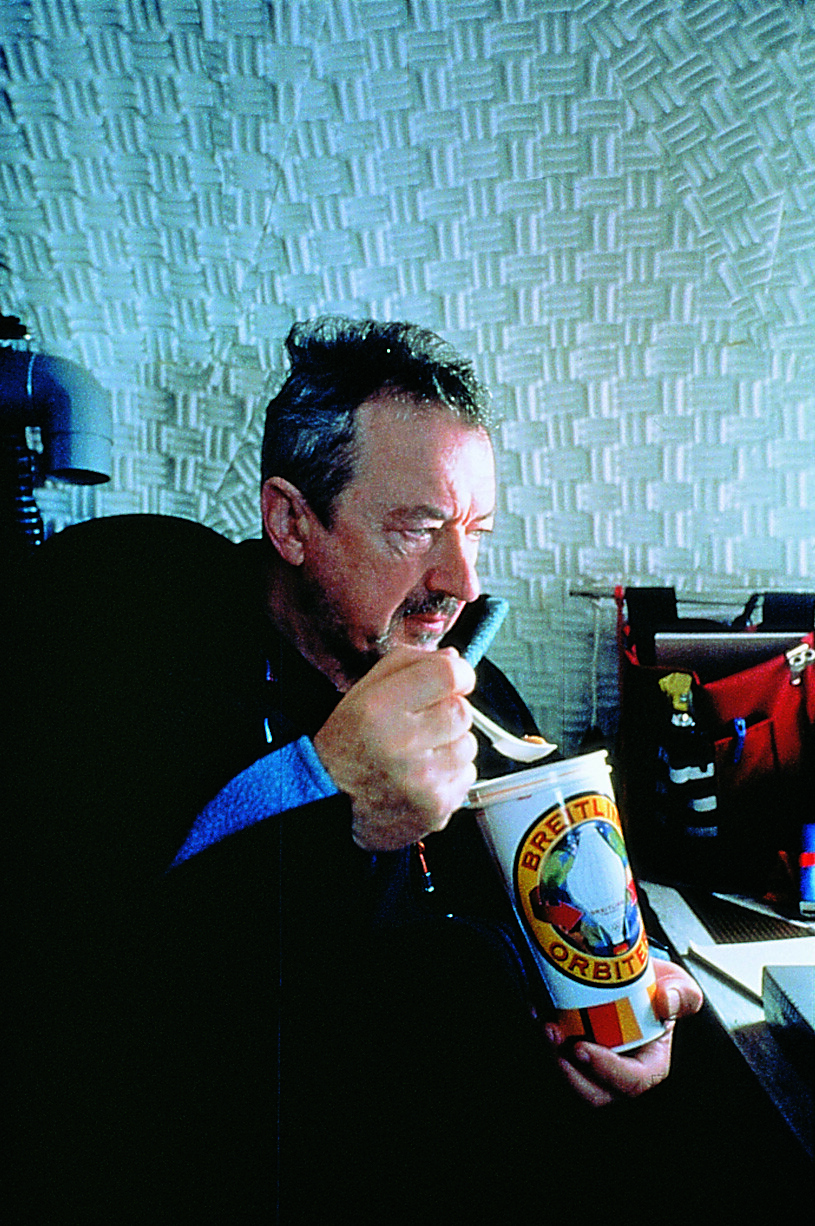

We quickly calm down, and enjoy a nice truffle paté we had stored for this special occasion. We still have panettone, Etivaz cheese, black bread and some margarine left.

Back in Geneva, the Breitling team is getting ready to take-off for Egypt. Alan, our flight director, gives us his last instructions :

"Fly high, then start your descent and drop the last empty fuel tanks."

I go to sleep, and waking up a few hours later I shout : 'Brian ! We forgot about the altitude record !'

Little did I know that Mister Jones had not forgotten, and he had beaten the record while I was asleep.

My last night in command is the most wonderful one. I am not scared of failing anymore. I feel like I am flying above the cockpit, above the balloon, looking to immortalise each and every second of this night. Soon, we will be surrounded by people, noise, madness. Now, I am alone with Brian sleeping, in silence, above everyone and everything.

Tomorrow is tomorrow. Now, in the darkness of the night, I let my thoughts wander. Peace of mind and heart.

Day 21

Landing is imminent.

At around 2am, we have 6 hours of fuel left and a clear instruction from HQ : do not land in the Great Sea of Sand. If we did, the cabin would sink into the soft sand and it would take days to bring it out. No helicopter could land there without destroying its engine with the dust. Our target ? The oasis of Mut, less arid, where our team and Alan our flight director would be waiting for us.

At sunrise, we will start our descent towards Mut. HQ tells Brian :

Try to land as smoothly as possible. Please let us know when you do.

Do not worry, he replies, you'll be the first to know. Then I will tell Bertrand !

We had planned for me to be in the pilot seat for landing, and Brian managing the exterior. However, as I wake up, I see that he has already started the descent and that everything is going well, so we switch roles.

As we descend, the ice that had accumulated around the cabin and the ballon started to melt, causing huge drops of ice blocks on the cabin. As we loose the weight, we struggle to loose altitude. I open the valve to let the helium out, and we drop like a stone. Just then, another block of ice detaches itself from the cabin and we regain some altitude.

As I open the roof hatch and hop on the top to prepare landing, a waterfall pours into the cabin. We had kept it as dry as possible for 20 days, but now, we don’t care anymore. I try to pull up the solar panels but because of our lack of physical activity in these 21 days I struggle and Brian has to help me.

Landing in the valley we had targeted reveals to be impossible, as we fly over it. At 1000 m, we are still going too fast. Only at 300 m we manage to slow down.

The Breitling team is trying to locate us, with a chase plane. The pilots decide to land at Dakhla airport, but 10 seconds before touch-down they hear Brian calling :

"To all stations. Breitling Orbiter 3 here. Do you copy?"

The pilots, thanks to a crazy reaction time, re-accelerate and make their way towards us. We are only 100 km away.

We are getting ready for the final approach. We try to lock everything inside the cabin so nothing flies in our heads at impact. Brian tries to stabilise the cabin as much as possible, balancing the burners. Through the windows we cannot really see land, and while we are wondering how high we are I realise that we are only 10 meters above the rocks:

"BRIAN, WATCH OUT, HOLD ON, WE ARE GOING TO HIT THOSE ROCKS!"

Instantly Brian puts maximum power into the burners, while holding on to the rail above our bed, knees bent to absorb the impact. A colossal shock shakes the cabin.Fortunately we had our helmets on. Immediately, the balloon bounces up taking us 100 meters into the air again. We see that we chose the worst spot to land : surrounded by sand for hundreds of kilometers, we have only rocks right below us. Alan on the radio :

"5 out of 10 for that first attempt!"

From the plane, they are taking the only external pictures of our landing that exist today. This time, we almost don't feel the impact with the ground. We bounce one last time, we get dragged in the sand over a few meters and we stop.

We look at each other. In silence. Total silence. It's a few seconds past 6am, Sunday March 21st. We fax HQ:

"Eagle has landed. Everything is ok. It's great."

We've done it. We landed. History made.

We walk out, in the middle of nowhere. The red cabin, fluorescent in the rising sun, is resting on the sand. The silver balloon is still floating above us. My boot in the sand leaves a trace that, obviously, reminds me of Neil Armstrong. While for him, it was incredible to step on something so far away from Earth, for me it was unbelievable to step on it again.

That's when the emotions hit. I start to run away from the cabin, trying to film the balloon before it's completely deflated. I start to talk outloud, looking at the sky:

It's incredible. Thank you, thank you!

The Breitling plane flies just above our heads, I shout and waive at the team. I am smiling like a little kid.

In seven hours, we will be rescued by an Egyptian helicopter, brought back to the crowd of journalist surrounding our families, before several days of celebrations.

But for now, we are still here, in the middle of an immense desert. There is no one around us to share our victory with. Silence all around us once the plane is gone. We could have stayed like this for long, feeling the wind on our face for the first time in 20 days, this wind that had carried us all around the world. Just seizing the moment.

On March 21st 1999, in the middle of the Egyptian desert, we completed the first ever non-stop ballon flight around the world.

We had succeeded. Thanks to our team. Thanks to the winds of life.